Archive

Beware the fiscal drag…?

Even Edward Luce at The Financial Times seems to be caught up in fiscal hysteria, claiming in the paper today that the fiscal cliff is acting as “a drag on the US recovery”.

Luce links to another FT article to support this comment, which is not the main thrust of the article but underpins a great deal of it — the idea that the debate is somehow ruinous to the economy and that averting the fiscal cliff is do-or-die moment.

Failure to get at least a two-year reprieve would set up a far more dangerous showdown for 2013 that could make last year look like a dress rehearsal.

However, the article Luce links to cites improved data and weaker consumer sentiment. One is an observable fact and the other is, well, sentiment. It’s hardly surprising that the obsessive media coverage of the fiscal cliff has disturbed folk. But there’s no evidence that businesses are similarly concerned or that the war of words has “acted as such a drag on the US recovery”. (Note the past tense.)

No reasonable person expects the fiscal cliff to have any meaningful effect. The tax cuts will be extended one way or another. The spending cuts will never materialise. Life will go on.

This whole debate is pure politics. It’s important in establishing the pecking order in Congress, perhaps, but has nothing to do with economics.

Consider the positions:

Obama wants to focus on recovery and jobs, ie stimulus, rather than worrying about debts and deficits. Yet he’s the one demanding increased government revenue!

The Republicans are intensely worried about America’s debt burden, yet they’re the ones blocking even modest revenue hikes!

None of it makes much sense…

Boehner tries Brezhnev gambit on fiscal cliff

Republicans would have to be crazy to let America go over the fiscal cliff. Which means that the big question in US politics right now is: Just how crazy is the GOP?

This might not be an accident. It could be a negotiating strategy, a bold piece of brinksmanship — the kind of tactic that renegade nuclear submarine captains tend to favour, if you’ve been watching ABC’s new geopolitical drama Last Resort.

This is Captain Marcus Chaplin rationalising his decision to threaten Washington DC with a nuke in the season premiere:

Ronald Reagan fires all the air traffic controllers. And his guys come to him and they say “Mr President, why did you go and do such a thing. Everyone’s going to think you’re crazy.” And Reagan… he points out the window of the Oval Office, towards Russia. And he says “That’s right. That is exactly what I need that bastard to think.”

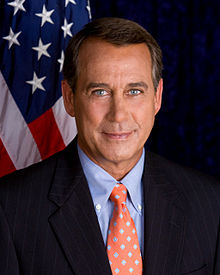

House speaker John Boehner seemed to be channelling Reagan on Fox News Sunday, when he made it clear that he considers spending and the debt to be a bigger problem than the fiscal cliff.

WALLACE: And, again, you kind of didn’t answer it the first time, what are the chances we’re going to go over the cliff?

BOEHNER: There is clearly a chance. But I’m going to tell you, I might be an easy guy to get along with — affable, obviously, I’ve worked in a bipartisan way on a number of agreements.

But I’m going to tell you one thing, Chris — I’m determined to solve our debt problem. We have a serious spending problem and it’s going to be dealt with.

He said this three or four times: his only concern is dealing with the debt. Yet when asked about what spending cuts he actually wants, he pointed to Paul Ryan’s budget proposals. The same proposals that Mitt Romney ran on and lost last month.

He also trotted out the same debunked nonsense about saving hundreds of billions by capping deductions, without having the courage to say which deductions Republicans would like to cut. Mortgage support, charitable donations… no comment. There are a “dozen different ways” to get there, he reckoned.

This is Reagan’s Brezhnev gambit. Except that, instead of acting crazy to protect the country from commies, Boehner’s doing it to protect America from a nonexistent debt crisis — and to save the rich from paying a bit more tax.

Treasury secretary Tim Geithner was on the show earlier, presenting the Democrats’ suggestions, which included stimulus spending and tax hikes for top earners. Not much red meat for Republicans, but lots of details and specific plans.

Clearly, the Democrats have no intention of making it easy for Republicans by proposing spending cuts. Why should they? They just won the election by running in opposition to the Republican vision of austerity.

Hence the crazy card from Boehner. The alternative is a political impossibility: lay out a detailed plan of the actual cuts Republicans would like to make. Boehner knows he can’t win that argument, because he knows the Republican position is pure political theatre.

This is hardly comforting for Americans. Boehner cannot win from this position, but he can inflict a defeat on his enemy — even if it means blowing up himself and the rest of the country at the same time.

And without giving too much of the plot away, it’s worth pointing out that Captain Chaplin ends up firing one of his nukes at Washington for real. If you’re gonna act crazy, you’ve gotta make the other guy believe that you’re serious about it.

It worked. The politicians backed down and the missile sailed 200 miles past Washington and exploded harmlessly(?) into the Atlantic.

That may end up being prophetic — because some critics reckon the fiscal cliff is more of a damp squib than a nuke.

The Cato Institute, for example, argues that automatic cuts to the defence budget could actually be good for the economy in the long run, and some market monetarists agree — as long as the Fed counteracts any fiscal shocks with appropriate monetary policy.

Of course, if it’s true that fiscal policy is largely irrelevant, it makes the fiscal cliff debate even more absurd. Sit back and enjoy…

China’s imbalances threaten plans for global domination

Charles Dumas of Lombard Street Research reckons China will suffer for not tackling its imbalances.

That’s probably true, of course, but like so many other analysts he seems to be comparing China’s problems to those of Japan in the early 1970s.

Domestically, China continues to build up its own bubble of debt that will probably never be repaid in full. And its refusal to reverse the policies that underlie this build-up is why its growth may halve to 5 per cent in the next few years. Without a sharp shift of policy, that 5 per cent may be the upper limit of Chinese growth for the long term, with a plague of banking crises threatening a worse result. This would be a disastrous result for a country whose per capita GDP (at comparable prices) is just 17 per cent of the US level, versus 67 per cent in 1973 in Japan, when its growth likewise halved to 5 per cent.

The article doesn’t explain the logic of comparing Japan in 1973 to China in 2012. This is odd, because it’s the only real indication of what Dumas reckons is in store for Chinese economic growth — he’s saying that in the future, over an unspecified period of time, China will grow half as fast, compared to an unspecified period in the past.

Nate Silver he ain’t.

Even so, this looks like wishful thinking. Japan’s economy was not significantly imbalanced during the two decades running up to 1970, so there’s little reason to assume that the re-adjustment thereafter is a useful comparison for China today.

A far more sensible yardstick is Japan in the late 1980s, as Michael Pettis wrote a month ago.

The most popular reason for comparing China with Japan of the 1960-70s is that China today is much poorer than Japan in the late 1980s. Japan in the late 1980s was rich, people will say, while China is terribly poor, so there can’t be any useful comparison between Japan in the 1990s and China in the next decade.

This, of course, is silly. If you are arguing about the consequences of imbalanced, investment-driven growth, it isn’t the nominal levels of wealth that need to be compared. After all there are rich as well as poor countries that suffered from this kind of unbalanced, investment-driven growth, and all of them ended up suffering subsequently from the same kinds of economic rebalancing.

What really matters is the extent of the underlying imbalances and the relationship between capital stock and worker productivity. In that light it is just as easy for a poor country to have excess capital stock as it is for a rich country – perhaps even more so.

Many big investors can’t accept this view. They have huge investments in China, they’ve opened offices there, they’ve lobbied the government for licences and quotas, and are committed to a growth rate that justifies this level of investment.

It’s the same with the investment banks. They’re not making any money in China these days, but they’re institutionally geared to being there. Bankers who earned their stripes doing mega Chinese IPOs for the past seven or eight years are now in senior positions, making it extremely difficult for those institutions to change course.

This is how Pettis describes the Japanese imbalances:

- Japan in the late 1980s grew at extraordinary rates fueled by a credit-backed investment boom funded at artificially low interest rates.

- Although for many decades much of the investment may have been viable and necessary, by the 1980s investment was increasingly misallocated into expanding unnecessary manufacturing capacity, as well as fueling surges in real estate development and excess spending on infrastructure.

- Artificially low rates, set nominally by the central bank but in reality by the Ministry of Finance, and coming mainly at the expense of household savers also fueled a bubble in local assets.

- An artificially low currency fueled very rapid growth in the tradable goods sector while also constraining household income growth.

- Because the growth model constrained growth in household income and household consumption, it forced up the domestic savings rate to extraordinary levels.

- The combination of low consumption and excessive manufacturing capacity required a high trade surplus in order to balance production with demand.

- And finally, and most worryingly, debt levels across the economy began to soar as debt rose much faster than debt servicing capacity.

Remind you of anywhere?

Of course, I don’t know who is right or how things will turn out in China, but I don’t think the big financial institutions are working very hard to challenge their optimistic forecasts. They’re wedded to the dominant narrative of China rising rapidly to take over the world, and clearly feel they have to be there at all costs (which, in effect, means burying their heads in the sand and hoping everything works out).

Meanwhile, many investment banks made more money in Malaysia (population: 30 million) than in China this year. Watch this space.

Mooching from Krugman

Paul Krugman has some interesting data on the moochers debate.

So I’m doing prep work for classes next semester, and I thought I’d just graph government transfer payments other than Medicare/Medicaid as a share of GDP. Here’s what it looks like:

This neatly shows that the size of government responds to people’s needs. Just as it should.

Economics is disappearing up its own differential equation

Once upon a time, economists spoke English and wrote books that provided real-world advice for business owners. Nowadays, they speak gobbledigook to one another while everyone else ignores them.

That, at least, is one person’s lament. Writing in the Harvard Business Review, Ronald Coase argues that it is time for economists to come back in from the cold.

It is time to reengage the severely impoverished field of economics with the economy. Market economies springing up in China, India, Africa, and elsewhere herald a new era of entrepreneurship, and with it unprecedented opportunities for economists to study how the market economy gains its resilience in societies with cultural, institutional, and organizational diversities. But knowledge will come only if economics can be reoriented to the study of man as he is and the economic system as it actually exists.

Coase claims that Adam Smith was widely read by “businessmen” of the day, by which he presumably means that today’s businessmen cannot understand today’s economists.

I’m not sure I buy any of that. It seems to me that economics is more accessible than ever before. From books like Freakonomics through to blogs and podcasts and award-winning documentaries… there’s no shortage of material offering real-world insights to entrepreneurs and businessmen.

However, this is clearly not the mainstream of economics. Most of the jobs available to professional economists require a theoretical approach — they sit in an office and look at numbers.

Today, production is marginalized in economics, and the paradigmatic question is a rather static one of resource allocation. The tools used by economists to analyze business firms are too abstract and speculative to offer any guidance to entrepreneurs and managers in their constant struggle to bring novel products to consumers at low cost.

Anyway, it’s worth a read…

Krugman delights modern monetarists

The slightly kooky proponents of modern monetary theory are taking cheer from Paul Krugman’s post on the impotence of bond vigilantes.

Krugman has made this important observation in the past, but this time he spells out his reasoning, step by step, and the key points align closely with that of modern monetary theory (MMT).

Of course, Krugman is still far too mainstream for the MMT gang. The model he uses to demonstrate the power of sovereign currency issuers is not one they subscribe to, but he comes to the “right” conclusions so most is forgiven.

All this is both interesting and heartening. Clearly, Krugman has based his argument on the following observable facts:

1. The U.S. government is a currency issuer, not currency user.

2. The U.S. government allows the exchange rate to float.

3. The rate of interest under a flexible exchange-rate sovereign currency regime is set as a matter of policy rather than being market determined.

4. The U.S. government does not have large debt denominated in foreign currency.

Regardless of how he gets there, some in the MMT community see Krugman as popularising one of their most important insights. Will other mainstream economists agree with him?

Robbing Merv to pay George

A difficult one for Grauniad readers, this: Bank of England to hand over gilts interest payments to slash national debt, says Larry Elliott, the paper’s economics editor.

This is George Osborne’s idea, so it must obviously be a bad one. Cue a lot of conspiratorial stuff in the comments about how this will all end in ruin. Some even compared it to the creative accounting employed at Enron. Yikes!

But the Uneconomical blogger Britmouse has a more convincing theory:

The idea that we should be trying to hedge against “future losses” on the QE portfolio is totally crazy. The only case where the Bank makes losses on QE is when gilt prices fall significantly, and long term interest rates rise. The only case where long term interest rates rise is when nominal GDP is growing fast. When nominal GDP is growing fast, tax revenues will be growing fast. Getting to that point is (or should be) the sole aim of UK demand management policy.

You don’t hedge against winning. You hedge against losing. The government is already hedged against losing, having bought back a third of its own long term debt with zero-maturity liabilities, a.k.a printing money. So we don’t need to hedge against winning by issuing more gilts than necessary and hoarding the cash. We should instead instruct the Bank to try much harder to make massive losses on its investments; until they do, we’ll remain stuck with low growth.

Of course, conducting monetary easing and fiscal tightening at the same time is totally stupid. The bank is adding money to the economy through QE, as the government is removing it through austerity.